® ®

|

Kawasaki's Fantastic H2, an Introduction |

|

||

|

The Excitement Begins

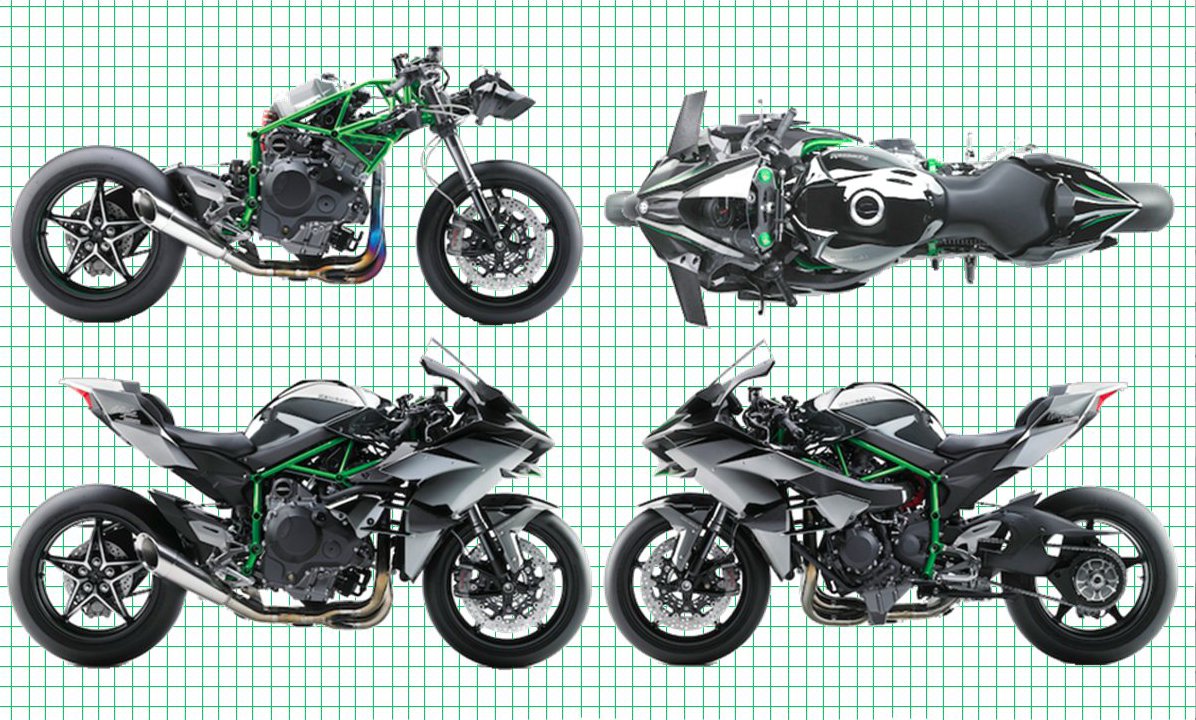

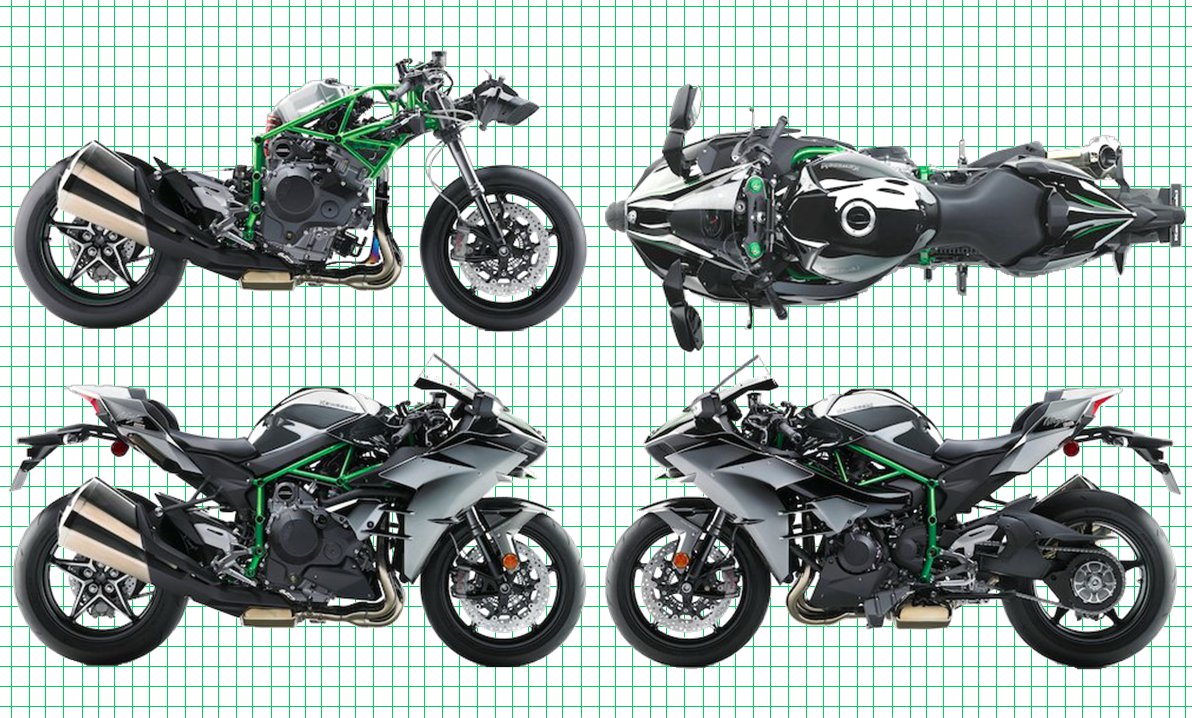

This is not to say Kawasaki incorrectly marketed the product. Though many of us at KMC felt that the bike should, in keeping with its performance personna and ineligibity for road racing, be a 1400 or 1500cc brute, KHI purposely chose to make it a 1000 so as to have the huge backdrop of an entire open class sportbike market against which the H2 would be contrasted and judged. As a result, though literally owing nothing to Kawasaki's ZX-10R, the H2 has much of the 10R's overall architecture. The H2 has generated an immense amount of buzz. Cycle World magazine penned an exclusive article that was embargoed until November 4, the date of the complete announcement at EICMA in Germany, and they released their online article on that very day, though a smaller "heads up" article came out a bit before that. KHI was pretty canny about the H2, releasing a series of "teaser" videos on ninja-h2.com, one at a time, over a period of months, each video revealing just a bit more, until the last several (there were 26 in all) openly communicated about the product. Jay Leno and Ricky Gadsen also eventually got into the act, with videos of their own. So much was the hype generated and so slowly was information about the bike released to the public, that in the early days someone on Facebook posted a $1000 offer for just a picture of the bike. |

|

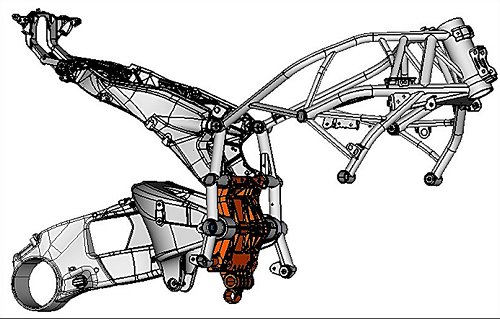

Equally interesting is the way the H2 and H2R were developed. Instead of building a hot rod that was streetable, and then amping that up to racetrack level, KHI did the opposite. They focused on building the bike they could build if there were absolutely no restrictions, no regulations, and it wasn't until that was done that they then embarked on making a street legal version. Two things resulted from this. First, and most importantly, I believe it resulted in a sharper focus on performance than would otherwise have been possible. Secondly, it made the spun-off road bike a much better product; the two bikes are very very close performance-wise, with the road bike retaining a remarkable amount of the balls-out character of the track model. Interestingly, there are literally only eight major performance parts separating the two bikes. This methodology was repeated in the marketing strategy. KHI's original plan was to announce the R model as a stand-alone bike, with no mention of the street model. Everyone would assume there was only one bike, and then months later Kawasaki could announce the road bike as an alternative for those who felt they couldn't commit to owning a track-only machine. A neat idea, but the fact of the road bike's existence immediately leaked out overseas and by the time of KMC's official November 4 press release the two-stage intro had been abandoned. Retained however is the ethic of this bike being a one-off build, an elitist's motorcycle choice. The H2 has no flooring plan, and U.S. and Canadian dealers are strongly discouraged from having a bike on the sales floor. This is part deliberate exclusivity and part necessary planning on KHI's part. As customers submit deposits to their dealers (10 percent, non-refundable), KHI builds bikes accordingly. No more and no less.

What Makes the H2 Special The H2's Reason for Being |

|

|

Not Your Average Sport Bike

Both bikes produce over 20.5 psi intake boost for a total of over 35 psi inside the airbox. The R model makes 326 PS, equal to 321 hp, the road bike 210 PS, or 207 hp. The last few hp in each case due to the ram air system. The R model weighs just 476 lbs, the road bike just short of 50 pounds more, for 525 lbs. This gives the R model a power-to-weight ratio of 1:1.48. For perspective, Ford's V-8-equipped F150 produces the same horsepower but weighs almost 12 times as much as the H2R. Thus the Ford would have to make 3900 horsepower to have the same power-to-weight ratio. Think about that for a moment. When it comes to acceleration, power-to-weight is all-important, and remember, the H2 is all about acceleration.

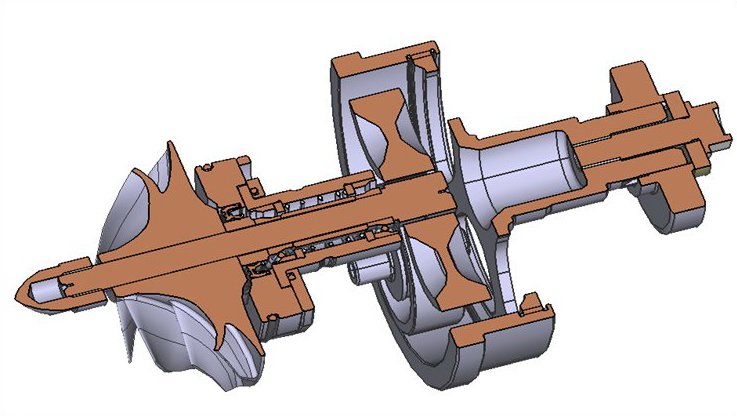

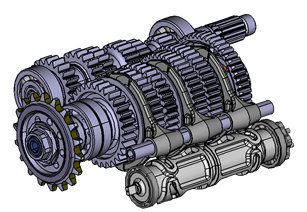

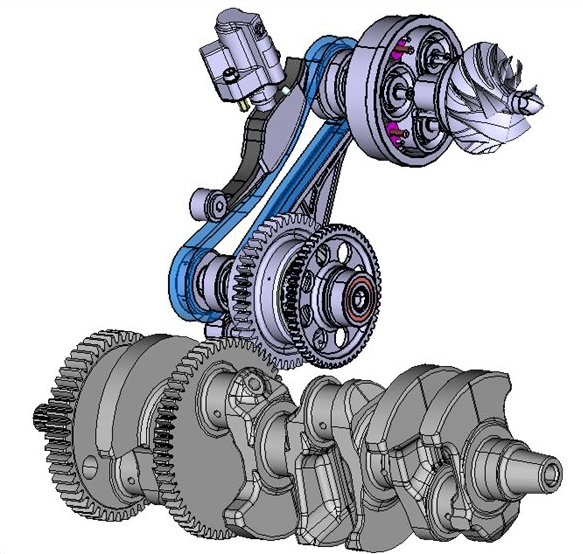

Intake and Supercharger

The supercharger is arguably the most interesting piece in the bike. Not terribly technological in itself, it is its solution to a well-known problem that is intriguing and startling. You see, centrifugal superchargers are not known for being all that user-friendly. They are basically turbochargers that are mechanically driven instead of exhaust driven, thus the centrifugal supercharger avoids at least one of the three problems inherent with turbos, the varying density of exhaust gases. It does not however avoid the second big disadvantage of centrifugal superchargers, and that is the fact that they are not positive displacement, that is, they do not move the same amount of air with each revolution, as does the more conventional Roots type supercharger. So it has that against it, as compared with the types of supercharger found in say, the Chevy Corvette, or for that matter, Kawasaki's own Ultra series supercharged personal watercraft (which actually use a smaller version of the Corvette unit, even made by the same manufacturer). Moreover, the third problem with centrifugal superchargers is that they, like turbos, inherently require a lot of rpm to move any air at all. They take time to spool up. Kawasaki attacked this last issue with the out-of-the-box solution of a built-in planetary gearbox, as part of the supercharger. This gearbox speeds up the supercharger's impeller shaft some eight times, which added to the gear and chain drive system coming into the gearset, results in an almost 1:10 overall supercharger drive ratio (specifically, 1:9.18). This is such a simple answer to the rpm problem that it is at once elegant and stupendous. KHI apparently has some experience with planetary gear systems as it builds them in its jet plane engines. But what it means to us is an awesomely high speed supercharger, whose impeller spins at well over 130,000 rpm! Now think of it. At idle, the supercharger's 5-axis CNC machined impeller is already turning almost 10,000 rpm! Incredible!

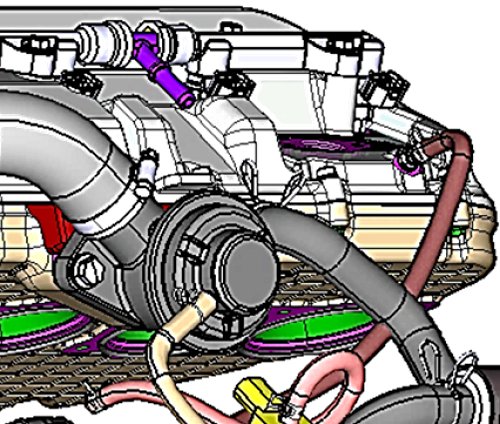

Despite the 20.5 psi boost (higher than even the company's 17.4 psi Ultra watercraft) the H2 and H2R do without an intercooler, a fact that Cycle World's Kevin Cameron found alarming (see his three videos on the H2 on the magazine's website). Kawasaki Japan has given three reasons for not using an intercooler, none of which involve the weight penalty, but you have to believe that was a factor (the intercooler in the Ultra watercraft is huge, larger even than the boat's supercharger). First, it is said that the supercharger, designed and built by KHI in-house, is inherently free from heat-producing compression within itself. This property of centrigugal superchargers is in fact well known, and therefore makes sense. Second, we are told that the ram air tube is carefully designed so that the intake air's density and speed lend themselves to keeping the air temperature low. Third, there is the bike's aluminum airbox, which while designed for maximum sealing also has an undeniable heat sink effect, drawing heat out of the compressed air. The supercharger's construction is otherwise fairly simple and is amply illustrated by a cutwaway drawing that shows how rotational motion comes in on the chain sprocket, moves along the shaft, goes into the planetary gearset, then into a bearing, and on to the supercharger's impeller. The bearing is an interesting piece. A plain bearing, it floats in oil, having oil on both its inside and outside surfaces. This serves three purposes. One, it allows the bearing to find its own rpm, thus limiting the shaft-to-bearing friction. Honda used this same technique in their 1982 and 1983 CX500 and CX650 Turbos, in which the turbocharger's bearing spun at half shaft speed. Second, the oil surrounding the bearing lends a cooling effect. And third, the oil serves as the system's shock damper, that is, it accepts and dissipates harmful load peaks arising from abrupt use of the throttle. The picture of the overall supercharger drive system shows crankshaft to gear to chain to supercharger shaft, to planetary gearset to impeller. Note the chain and chain tensioner. The drive system made up of gear and chain is lubricated by no fewer than three separate oiling points, including two directed on just the link plate type chain. The chain's tensioner, like most today, is hydraulicly assisted.

Airbox and Throttles

The throttle bodies are unique among Kawasaki products by being bolted onto the engine and not spigotted as is the usual practice. Dozens of bolts hold down the injectors, through a layer of rubber suspension, to the cylinder head. Incidentally, the throttle bodies must be removed for periodic replacement of the supercharger's oil gallery filter. The huge 50mm (i.e., two inches, larger than ever used before on a Kawasaki sport bike) throttle bodies are single throttle instead of the usual sportbike dual throttle, but still retain the sport bike oriented dual injector system, the upper injectors chiming in at very high engine rpm (complementing ram air) and ultimately contributing over 70 percent of the total fuel delivery at extreme high rpm. The upper and lower fuel injectors are both 4-hole units, as opposed to the 8-hole and 12-hole type used on other Kawasaki products. The Keihin throttles are ride-by-wire, or as Kawasaki calls it, Electronic Throttle Valve (ETV), a system Kawasaki has already used on two other products. ETV is used on the H2 for two reasons. First, to provide the obligatory top speed control on the road model. And second, to support rider assistance electronics such as traction control and power modes, on both bikes. The throttles are on the parts block list, a list kept at KMC as a filter through which users much go to buy parts. Because the R model uses non-street-legal parts that the company does not want to show up on the street, an H2R owner must show documented proof of ownership to buy certain parts. The blocked H2R parts include the ECU, the camshafts, the exhaust, the fuel pump, and the throttle bodies, which incidentally must be programmed into the ECU if they are ever replaced.

Ignition Bottom End Lubrication and Cooling

The cooling system on the H2 begins with a radiator that is the same size as the one on the ZX-10R but not the same radiator at all. Instead, it is made to a racing design that allows it to be more efficient and together with the bike's special cowl design results in 50 percent greater cooling ability. Don't forget the oversize thermostat and the special added cylinder head cooling passages also.

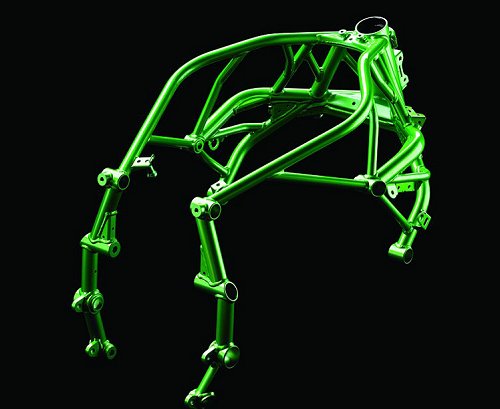

Exhaust Transmission Frame and Swingarm Chassis Geometry Body Suspension, Wheels, and Brakes

The bodywork on the two bikes varies considerably. Both utilize the new-for-Kawasaki black chrome paint, which is said to be hand applied except for the final layer which is robot-applied, and is not with present technology repairable. And although they look similar, the cowls on the two bikes are not interchangeable, being differently shaped and having different windscreens. The R model's bodywork (except for the rear fender) is of course all carbon fiber, and simply beautiful, with deep, shiny gel coat. Plenty of aerodynamics abound on the two bikes, with a bit more on the track bike, but both have lots. The track bike has two sets of wings, one with downturned "winglets," same as on a jet plane. The wings add downforce and actually work, as proven by top speed runs in which they were removed to get 5 more mph. The aerodynamics continue with the presence of "Gurney flaps" (Google it), small ridges on the topsides of the wings (and on the mirror stalks of the road bike) which assist the downforce effects and were first used by car racing legend Dan Gurney.

Electrical Electronics

Rider Assistance Electronics, that is, electronics designed to make the experience equally inspiring across a broad spectrum of riders' abilities, are a large part of these two bikes. KTRC, Kawasaki's traction contol, offers a range of increasingly more controlling settings, beginning with levels of control that allow wheel slip under some conditions (such as roadracing) and ending with settings which do not allow wheel slip under any circumstance. Unique to this model, Kawasaki has incorporated a system similar to that Tom Sykes had on his 2013 World Superbike championship winning race ZX-10R, which adds in-between steps to the standard three KTRC settings, so that the H2 rider actually has nine choices overall. KLCM, Kawasaki Launch Control Mode, borrows from Kawasaki's motocross bikes a system that allows the rider, once it is set, to hold the throttle to max and focus on his holeshot, while the system pulls up a special ignition/fuel map that demphasizes horsepower and emphasizes torque, for best takeoff result. It also shuts off automatically at third gear, just as on the motocross bikes. Much more sophisticated than the KX250/KX450 system however, the H2's KLCM limits the engine rpm to 6,500 and monitors engine heat and cycles down and eventually shuts completely off in the event the system is over-used. KEBC, or Kawasaki Engine Brake Control, when turned on lessens engine braking by slightly increasing throttle opening, a system that the current ZX-10R has also and which functions through that bike's dual throttles, whereas the H2's system works through ETV. Rain Mode, which is available only on the road model (the owners' manual for the R model warns, "Do not ride in the rain..."), is actually a power mode with a new name. When activated, the road bike's power is reduced some 50 percent, and at the same time KTRC Mode 3, its most intrusive setting, is activated, for good measure.

Maintenance Tools and Accessories Summary |

|

|

Cycle World article

|