Why do I like the CB500? I'm a little crazy, I guess! Between 1976-1977 I wrenched at Bill Robertson's Honda in North Hollywood, a big, well-known once-Triumph-then-Honda-and-BMW dealer in the then still sleepy enclave of the San Fernando valley. A good place to work and a time when I was beginning to really enjoy being a mechanic. One afternoon I was handed a prepare-for-sale work order for a 1972 CB500 Four that was in the dealership's used bike inventory, where about ten of these machines languished after having been rescued from a rental agency in Japan. On a whim I bought one of the others and prepared two identical bikes for sale that day, ultimately managing to put over 85,000 miles on mine before selling it in 1980 with 92,000 miles on. You can bet that bike got the best mechanical care. About every 60 days, an hour before going home at the end of a Saturday, I would roll my bike onto my lift and service it completely, axle to axle. I remember being more and more satisfied with the sound and feel of the bike each time I tuned it. I still feel that way today. I really like this bike. What do I like (and dislike) about the bell bottom era CB500 Four? Here are my thoughts.

Why do I like the CB500? I'm a little crazy, I guess! Between 1976-1977 I wrenched at Bill Robertson's Honda in North Hollywood, a big, well-known once-Triumph-then-Honda-and-BMW dealer in the then still sleepy enclave of the San Fernando valley. A good place to work and a time when I was beginning to really enjoy being a mechanic. One afternoon I was handed a prepare-for-sale work order for a 1972 CB500 Four that was in the dealership's used bike inventory, where about ten of these machines languished after having been rescued from a rental agency in Japan. On a whim I bought one of the others and prepared two identical bikes for sale that day, ultimately managing to put over 85,000 miles on mine before selling it in 1980 with 92,000 miles on. You can bet that bike got the best mechanical care. About every 60 days, an hour before going home at the end of a Saturday, I would roll my bike onto my lift and service it completely, axle to axle. I remember being more and more satisfied with the sound and feel of the bike each time I tuned it. I still feel that way today. I really like this bike. What do I like (and dislike) about the bell bottom era CB500 Four? Here are my thoughts.

Pluses:

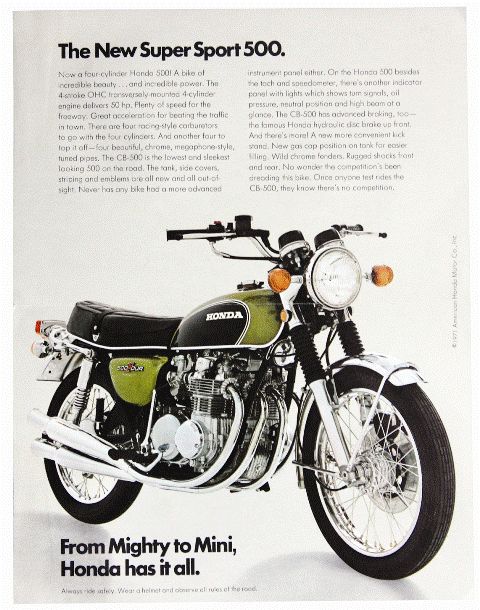

- The appearance. Having come of age in the raw, exposed-engine period of motorcycling, I was naturally one of those who as a teen sat on and daydreamed about the used Shovelheads at the downtown Harley dealership. I therefore appreciate the classic lines that once characterized motorcycles. The CB500 is a throwback to that era and one of those bikes you just like to look at. It is so appealing, its lines so correct, so right. The four exhaust pipes were probably considered an extravagance in their day, but today they're simply gorgeous. The bike's curves, its proportions. And just enough body panels to please the eye. Beautiful. The CB500 has to be one of the top ten most beautifully styled bikes of the 20th century, and I understood completely when I discovered that the CB500 and early CB550 are very popular in Italy, where asthetics are kind of a national ethos. It's a shame the bike is comparitively so little appreciated in the states.

- The ergonomics. Though 6'-1" and therefore a bit outsized on many bikes, surprisingly, I feel more at home on the CB500 Four than on any vintage machine of any size I have ridden. It just feels right. The bar-to-peg-to-seat geometry simply works for me and works well.

- The simplicity. When I retired from corporate work, where I was responsible for dealer training and therefore knowledgeable in the latest technology found on bikes today--ABS, traction control, gyro stability systems, electronic engine power scaling, laptop-based servicing--I looked forward to being around machines again that were more elemental. Technology has its place, and has unarguably enhanced motorcycling for the vast majority of riders. But my version of the sport appeals at a simpler level, and I appreciate machines that exhibit what is now a rare consideration for simplicity and ease of maintenance.

- The light weight. I put more than 40,000 miles on my CBX1000, rode a ZG1400 Concours daily for over a year, am still an ardent fan of the early Gold Wing and have, being in the business life-long, ridden many many motorcycles. But my learned take on motorcycling says relative lightness is a virtue. To a point, of course--I'm not enthused about mopeds (though I think scooters are a good, efficient, socially-responsible form of transpo). And happily, that point pretty much hits its bullseye in Honda's CB500 Four.

- The handling. Undoubtedly owing largely to its light weight, but surely a product of happy geometry as well, muscling this bike around curvy roads doesn't actually take much muscling. It's neutral-feeling, responsive, natural. It's reminiscent of a pushrod Brit twin in that respect. The chassis is invisible. It's just you and the throttle.

- The quality. I'm not going to say modern bikes are not made well. They certainly are. But many of us consider the late 1960s and especially the early 1970s Honda's golden age, a time when the company's products were at their zenith. They're just incredibly well-conceived and manufactured. Overbuilt, really.

- The steel. Related to the above, I prefer a bike with steel fenders. More substancial-looking, classic, durable. And of course that exhaust. I don't like chrome much, but I accept it in the fenders and exhaust because it represents something that plastic doesn't.

- The practical design. How many bikes have a grab rail with which to centerstand the machine? How many even have centerstands? Have you ever seen a more practical fuel cap? A drum brake that actually works. The petcock on the left side where it belongs. Beautifully practical fork protective gaiters. Easy-access oil drain plug. Steel fenders, full-sized footpegs, naturally-flowing lines (no spaceage angularity here). Whole. Integral. Beautiful. Inspiring.

- Engine access. A significant plus to me is that the top end of the CB500/550 engine can be rebuilt in the frame. This was taken for granted of machines of that era, and it is very advantageous that Honda made this decision, especially in light of the 750 not benefitting in that way. It is even more fortuitous because all these bikes need top end work.

- Serviceability. Related to the above, that is, how easily the engine is accessed, is the simple joy of maintaining a motorcycle that seems designed to be maintained. Doubtless part of the enjoyment for me is my long history with the model. But even beyond that, I can't think of a Honda that is more fun to work on, where every part falls so readily to hand.

- The visceral. Possibly indefinable and subjective, but real. Honest communicators in the powersports industry take stock in the overall feeling of the motorcycle. Weight and balance and turnability and stability and the almost subconscious flux of braking, acceleration and subtle body movements. Countersteer, the controls all working together, the rhythym of it, the choreography. It's a magic mix, and the CB500 has it all. Even the bike's sound is right.

- The electrical system. There are motorcycles right now, fifteen to fifty years younger than the sohc Honda fours, for which quality replacement batteries are impossible to find. By contrast, the CB500/550 battery was used on several Honda models as well as some Kawasakis, which means this battery configuration should be around for a fairly long time to come; longer than it might have otherwise. The charging system is somewhat unusual in design, but there again, used replacement parts (preferred over new Chinese parts, thank you) are plentiful due to the quantity in which these machines were produced. And the charging system is very durable and has more than ample output, despite what forum "experts" say. The handlebar switches are metal, not plastic as on later bikes, and not as complex either. It's a simple system. On my 73 model at least, no sidestand switch, no starter lockout, no sensors or relays, no microprocessors, no always-on headlight, no impossible-to-separate connectors, no fuel gauge or gear indicator, no starting/headlight cutout, no irritating self-cancelling turnsignals--none of that stuff. The electrical system is made up of just what is needed and no more. I like that. I am not a Luddite, as a lifelong powersports professional I embrace technology. But I think technology for technology's sake is stupid and yet evident in much of current powersports. It has distanced us from something important and elemental about motorcycling. I ride a bike that has only one fuse! At the same time this makes me slightly nervous and it pleases me for its essential simplicity.

- The carburetors. Though adorned with an over-complicated and excessively springy throttle linkage, made of a somewhat fragile zinc-rich alloy, and lacking a fast-idle system (though on a well-tuned bike it is hardly necessary), the CB500/550 carburetors internally are about the simplest they could possibly be. Big holes and very few of them. Two jets. Four tunable circuits. Extremely easy to adjust. Nothing like the carbs on later bikes. Which means they are ridiculously easy to clean and maintain. I have access to all kinds of alternate carburetors and I still prefer the originals.

- The reliability. Take one of these engines completely apart down to the last bolt and you'll be amazed. Such elegantly simple yet admirably effective assemblies. Not asthetically handsome, not beautiful, not technical marvels, just cleverly designed and purposely overbuilt. Honda apparently learned a lot from their remarkable yet occasionally plagued twins of the 1960s. The early 70s fours are made surprisingly sturdy, very sensible, very solid. Honda certainly earned its reputation for reliability on such motorcycles as this CB500 four.

Minuses:

- The buzziness. The thing that most detracts from the CB500 ride is its characteristic 180-degree four-cylinder buzz. It is of course mitigated by using the higher gears, but there is no fun in that and the engine was not designed to mimic a dump truck. There's no squirt below 5,000 rpm. Fitting a 4-1 aftermarket exhaust also noticably reduces vibes, but at the expense of lost originality, a change in sound, and to me at least an impaired appearance. The best solution to the vibes issue is to enlarge the engine's cylinder bores so that its torque peak comes lower in the rev range.

- And that leads to the power question. Though this engine acquitted itself admirably against the mostly pushrod valve competition of its day, it is hard not to notice the bike's lack of power. And attempts to spin the engine harder to squeeze more out of it naturally just acerbate the aforementioned vibration. Thankfully, many have found it not very hard to get appreciably more power from the midsize four, and that with little if any downside.

- The shifting. I have written of this elsewhere. You know, riding a 50+ year old Honda four reminds me a lot of riding an old pushrod Brit bike. You make allowances for their quirkiness or you can't enjoy them. The CB500 is like this only in the area of shifting. I don't quite regard the CB500's shifting as a negative--I deliberately chose the 500 over the better-shifting 550. But it is something one has to come to terms with, especially when the engine is hot. And the more familiar you are with later model bikes, the more you will view the CB500's shifting as less than perfect. It is what it is. Having basically a 350 twin transmission means the CB500's trans is a pretty old design with function not as slick as that of the 550 with its later, better-engineered 750-spec trans. However, good tuning and maintenance--not to mention deliberate technique--all help considerably. As will the right engine oil. Owning a 70s CB550 is a commitment. Owning a 70s CB500 is a passion.

- The carburetors again. These are great carbs, flawlessly functional, easy to maintain, and even very adaptable to engine modification. However, each float bowl is attached with four tiny screws that are not very accessible on the bike. And even if they were, the combination of extremely soft metal threads and the unfortunate spring tension method of mainjet retention spells trouble for removing and replacing float bowls in-situ. Fortunately, removing and replacing these carburetors is not difficult. But, Honda's early through-the-screw method of bowl draining is just plain neanderthal. Incredibly messy.

- Worse still is the petcock, whose also very weak zinc-based metal makes it disappointingly low quality and prone to wear and leakage, not to mention potentially dangerous.

®

®

Why do I like the CB500? I'm a little crazy, I guess! Between 1976-1977 I wrenched at

Why do I like the CB500? I'm a little crazy, I guess! Between 1976-1977 I wrenched at