® ®

|

|

Prior to the Concours' emergence, Kawasaki had for several years dished up some innovative and tasty offerings in the KX250F and KX450F four-stroke motocrossers, the latter having carried first James Stewart then Ryan Villopoto to dominance in the class. The hottest of the hot Ninja 600, which returned in 2013 as the 636 -- the only Japanese middlewight sporter with traction control by the way, the superlative, industry-leading ZX-10R, the middleweight 2006 bike-of-the-year and flat track phenom Ninja 650, and the stylish 900 through 2000 Vulcan cruisers, the star of which, the 1700 series' Voyager, proudly flagships Kawasaki's feet-forward line. It's plain that Team Green was cookin’'! Since 2006 when Kawasaki brought out the long-rumored ZX-14 Ninja, a true out-of-the box 9-second asphalt-eater whose surprisingly-refined manners have not only made it the new heavyweight grudge-night contender, but also the all-around sweetheart in its class, still today's mega-Ninja, completely overhauled for 2012 with a stroked engine and even more power (and accompanied by an ad campaign that included head-to-head contests with Hayabusas and a lot of coddling by none other than world drag racing champion Ricky Gadson), Big Green seemed content with nothing less than domination.

Against this backdrop of success the Concours 14 shined ever more brightly. Emerging as a 2008 model but released a year early in 2007, the bigger Connie immediately demanded the top of the sport touring heap. The long-anticipated replacement for Kawasaki’s venerable ZG1000, the ZG1400 Concours showcased a number of technological treats that profoundly demonstrate Kawasaki’s desire to mold value into its products in new ways. Variable valve timing, an electronic key system, on-board tire pressure monitoring, and an articulated shaft final drive were just a few of the shining jewels in the Concours’ technological crown.

The Powerplant

The Concours' variable valve timing system moves the intake cam forward at low speed and back at higher rpm, to shape the power delivery as broad and as flat as possible. The key is the intake valve's timing.

With an engine taken straight from the Ninja 1400, one would have expected this then new sport tourer to have no lack of power. But it was unmistakeably clear that this machine had been designed for the long haul. To that end, Kawasaki’s engineers re-tuned the ZX’s 200-hp prime mover to a more manageable 155-hp for more civilized manners, largely by a 6mm shrinkage of its throttle bodies. In addition to the requisite recalibration of ignition and fuel injection to suit the Clark Kent-ish motor, the Concours engine differs from the Ninja also by having a revised version of the back torque limiting clutch found on the company’'s 600 sporter. Other than these changes, the engine is largely the same as that in the big Zed-X.

Variable valve timing

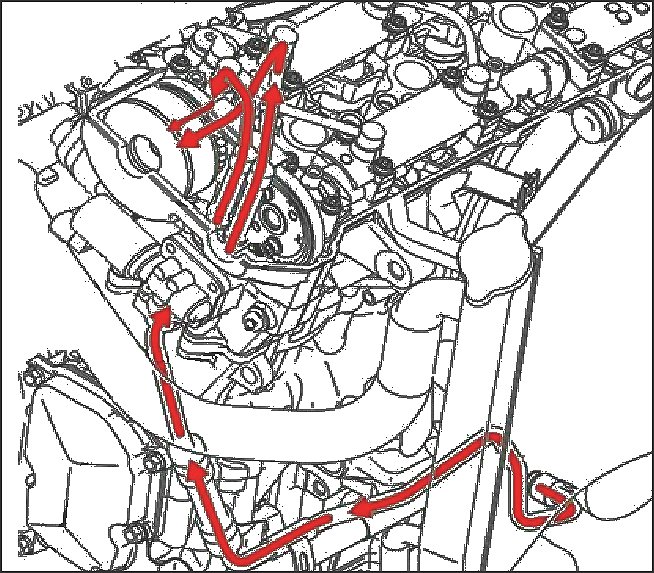

Pressurized engine oil is fed to a ECU-triggered shuttle (oil contol valve, or OCD) valve, which pushes, though a hydraulic drum, the intake cam forward, and though channels, back again. The OCD has its own ECU fault code.

Momentum’'s energy is spent as the air column travels down the manifold, slowing as it nears the open intake valve. Engine designers time the intake valve’s closing to coincide with the air’ column's eventual slowing and stopping, thus taking maximum advantage of the power potential. The problem is, with changes in rpm come other changes that make the ideal intake valve closing point vary. Kawasaki’s VVT moves the intake valve’s closing point forward and backward to ride or “surf” this ever-changing best closing time, thereby maximizing cylinder filling efficiency at a wider range of rpm. Though in recognizable use in the car world, it's the first time this technology has been implemented in a motorcycle.

The Concours’ intake camshaft is driven by a hydraulic drum that is itself rotated by the cam chain. This drum is fed two lines of oil pressure that have first passed through a computer-operated shuttle valve. The shuttle valve’'s position, determined by the bike’s ECU (through information from mostly the throttle position sensor), at any given moment favors one of these two lines over the other, resulting in camshaft orientation either ahead of (advanced) or behind (retarded) its central position at idle. The bottom line is that instead of the new Concours having the less midrange commensurate with its reduced top end, it is blessed with nearly the same midrange as its more muscular brother, offering much the same riding experience as the ZX but in a package better suited to long-distance use.

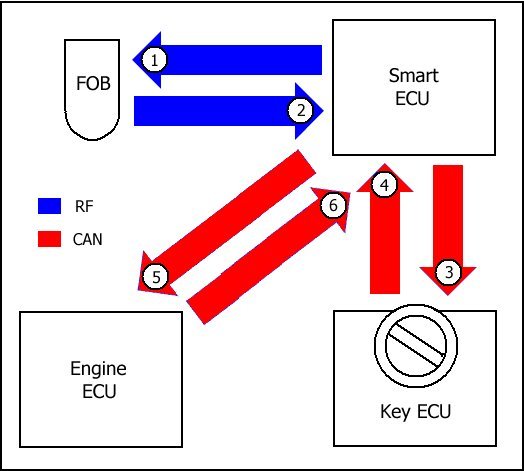

Smart ECU to keyfob and back to ECU, via radio frequency. From Smart ECU to keyswitch and back to ECU, via controller area network (CAN). From Smart ECU to FI ECU and back to ECU, also through CAN.

KIPASS

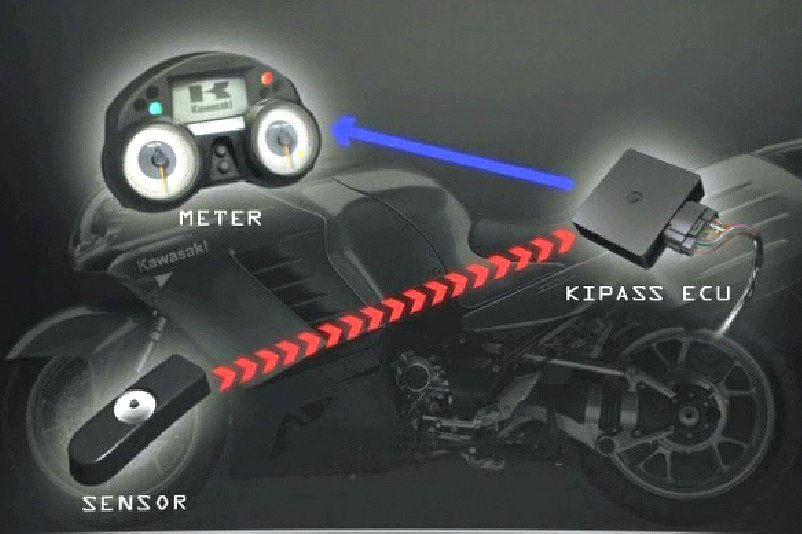

Tire pressure monitoring, TPMS. Special shrader valves commnicate via RF with the bike's Smart ECU. The Smart ECU in turn indicates the values on the bike's instruments, via CAN.

TPMS

Tetra-Lever

For a gearhead, this is a soul-stirring picture! Brawn, technology, structural beauty, balance, marvelous metal! Highlighting the monocoque frame and articulated drive shact, it is a visual treat for sure!

Add in optional ABS (back in Kawasaki’s U.S. lineup after a twelve-year absence); push-button windscreen height adjustment; a 10-amp fairing-mounted accessory jack; an easy shock preload adjustment knob; possibly the slickest quick-release saddlebags in the industry; the unmistakable and quite intentional big Ninja'’s geometry, ergos, and persona -- and it's hard to believe anyone could choose another sport tourer over this one.

In 2010, after all the magazines had named it best sport tourer, the Connie was revised with improved heat management, better tires and brakes, an electronic glovebox, traction control, grip warmers, and microprocessor control of its electronically-adjusted windscreen. Quite a machine!

|

|

Recommended reading: |

Last updated November 2022

Email me

© 1996-2022 Mike Nixon