® ®

|

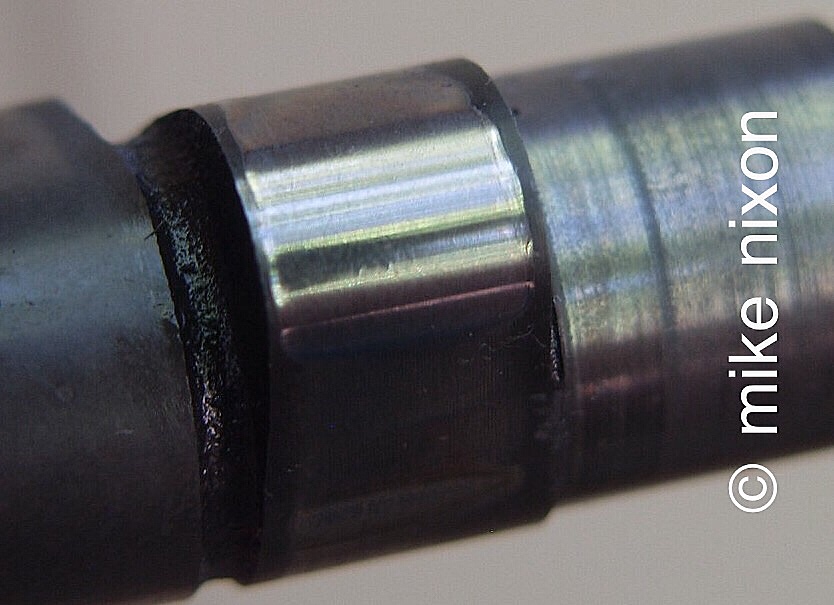

Cam wear |

This is a cam from a 1974 Honda CB350F, a smallish four-cylinder model that is one of the several single overhead cam (SOHC) 70s Hondas that are beginning to be very collectible right now. We're looking at one of the cam's lobes, and what is visible is a surprising amount of wear on this cam. This is not catastrophic, not excessive. No signs of excessive friction are visible. The engine was not run low on oil and there weren't any oil related problems. In fact, the engine is at this moment completely apart and there is no wear in the transmission or anywhere else. What gives? The angle of the camera acentuates the image somewhat. But the wear is more than most people would expect in just 4900 miles. That's right, 4900. And it's normal.

The fact is, camshafts in a good many engines from cars to motorcycles and even to piston-engined aircraft wear like this. Hondas can be observed to wear their cams at a rate between 0.001" to 0.003" per thousand miles, as shown in this example. Industry insiders know well that cams are not made the way people think they are. They're not extremely hard. They're not even moderately hard. With very few exceptions, a cam from virtually any Japanese motorcycle can easily be drilled with a standard HSS drill bit, the kind you can pick up at the bargain table at the hardware store. Yup. And when they see the kind of chips that fly out of that drilled hole, experienced machinists recognize them instantly. Cast iron! Yup. Most cams are cast iron or cast steel. And very soft. Below Rockwell 52 in fact, for you metallurgists.

It's a well-known fact. So what? Well, this explains something. It means that these vintage bikes with 20,000 to 40,000 miles have some significant wear on their cams. Enough to make them perform below their potential, demonstrably. In fact, the thing I see most often signalling this wear is valve timing quite a bit off from spec. Naturally, the typical 5 to 10 degree discrepancy can also be attributed to cam chain wear, but not in low mileage engines. This in turn means that in many cases folks who swap in aftermarket cams are very probably seeing gains not from the supposed advantages of said products but rather from the correction of the stock systems' wear or misadjustment. A new part brings the below-standard function to the standard, normal efficiency of a new unworn part. The same thing happens with aftermarket ignition systems. A stock ignition that was never properly serviced is replaced with an electronic system and the improvement is ascribed to the latter being a better system, when in reality it is not. It's simply that something was finally done to help the ailing motorcycle. Big bore kits, aftermarket carburetors, racing air filters -- all of them deliver improvements that are due much much more to correcting lack of maintenance than to the supposed superiority of these parts.

It is interesting in this connection to observe that a product being offered by companies normally thought of as high performance parts providers, namely camshafts welded up and reground to stock specification, are increasingly offered by big-name cam mongers Webcam and Megacycle, and are something of a well-kept secret. And they're really good, very useful, and very timely products. And just one more example of how the OEM applied carefully outdoes and makes irrelevant the aftermarket. Think of it: No matter whatever else you have done, how many new parts you have bolted on, how else can you complete your resto effort and the performance level the machine exhibited at its creation 30 to 40 years ago? A used stock cam won't get it -- most are worn as much or more than yours. A fresh cylinder bore won't, which you know if you know what passes for aftermarket piston rings today, and for that, given the almost suicidal frustration inherent in attempting to get expert cylinder machining.

Don't overlook the camshaft.

|

© 1996-2018 Mike Nixon